This session was part of The Memory of the World in the Digital Age: Digitization and Preservation conference and aimed to describe the initiatives of the Data at Risk Task Group (DARTG), part of the Committee on Data for Science and Technology (CODATA), a body of the International Council for Science.

This session was part of The Memory of the World in the Digital Age: Digitization and Preservation conference and aimed to describe the initiatives of the Data at Risk Task Group (DARTG), part of the Committee on Data for Science and Technology (CODATA), a body of the International Council for Science.

The goal is to preserve scientific data that is in danger of loss because they are not in modern electronic formats, or have particularly short shelf-life. DARTG is seeking out sources of such data worldwide, knowing that many are irreplaceable for research into the long-term trends that occur in the natural world.

Organizing Data Rescue

The first speaker was Elizabeth Griffin from Canada’s Dominion Astrophysical Observatory. She spoke of two forms of knowledge that we are concerned with here: the memory of the world and the forgettery of the world. (PDF of session slides)

The “memory of the world” is vast and extends back for aeons of time, but only the digital, or recently digitized, data can be recalled readily and made immediately accessible for research in the digital formats that research needs. The “forgettery of the world” is the analog records, ones that have been set aside for whatever reason, or put away for a long time and have become almost forgotten. It the analog data which are considered to be “at risk” and which are the task group’s immediate concern.

Many pre-digital records have never made it into a digital form. Even some of the early digital data are insufficiently described, or the format is out of date and unreadable, or the records cannot be located at all easily.

How can such “data at risk” be recovered and made useable? The design of an efficient rescue package needs to be based upon the big picture, so a website has been set up to create an inventory where anyone can report data-at-risk. The Data-at-Risk Inventory (built on Omeka) is front-ended by a simple form that asks for specific but fairly obvious information about the datasets, such as field (context), type, amount or volume, age, condition, and ownership. After a few years DARTG should have some better idea as to the actual amounts and distribution of different types of historic analog data.

Help and support are needed to advertise the Inventory. A proposal is being made to link data-rescue teams from many scientific fields into an international federation, which would be launched at a major international workshop. This would give a permanent and visible platform to the rescue of valuable and irreplaceable data.

The overarching goal is to build a research knowledge base that offers a complimentary combination of past, present and future records. There will be many benefits, often cross-disciplinary, sometimes unexpected, and perhaps surprising. Some will have economic pay-offs, as in the case of some uncovered pre-digital records concerning the mountain streams that feed the reservoirs of Cape Town, South Africa. The mountain slopes had been deforested a number of years ago and replanted with “economically more appealing” species of tree. In their basement hydrologists found stacks of papers containing 73 years of stream-flow measurements. They digitized all the measurements, analyzed the statistics, and discovered that the new but non-native trees used more water. The finding clearly held significant importance for the management of Cape Town’s reservoirs. For further information about the stream-flow project see Jonkershoek – preserving 73 years of catchment monitoring data by Victoria Goodall & Nicky Allsopp.

DARTG is building a bibliography of research papers which, like the Jonkershoek one, describe projects that have depended partly or completely on the ability to access data that were not born-digital. Any assistance in extending that bibliography would be greatly appreciated.

Several members of DARTG are themselves engaged in scientific pursuits that seek long-term data. The following talks describe three such projects.

Data Rescue to Increase Length of the Record

The second speaker, Patrick Caldwell from the US National Oceanographic Data Center (NODC), spoke on rescue of tide gauge data. (PDF of full paper)

He started with an overview of water level measurement, explaining how an analog trace (a line on a paper style record generated by a float w/a timer) is generated. Tide gauges include geodetic survey benchmark to make sure that the land isn’t moving. The University of Hawaii maintains a network of gauges internationally. Back in the 1800s, they were keeping track of the tides and sea level for shipping. You never know what the application may turn into – they collected for tides, but in the 1980s they started to see patterns. They used tide gauge measurements to discover El Niño!

As you increase the length of the record, the trustworthiness of the data improves. Within sea level variations, there are some changes that are on the level of decades. To take that shift out, they need 60 years to track sea level trends. They are working to extend the length of the record.

The UNESCO Joint Technical Commission for Oceanography & Marine Meteorology has Global Sea Level Observing System (GLOSS)

GLOSS has a series of Data Centers:

- Permanent Service for Mean Sea Level (monthly)

- Joint archive for sea level (hourly)

- British Oceanographic Data center (high frequency)

The biggest holding starts at 1940s. They want to increase the number of longer records. A student in France documented where he found records as he hunted for the data he needed. Oregon students documented records available at NARA.

Global Oceanographic Data Archaeology and Rescue (GODAR) and the World Ocean Database Project

The Historic Data Rescue Questionnaire created in November 2011 resulted in 18 replies from 14 countries documenting tide gauge sites with non-digital data that could be rescued. They are particularly interested in the records that are 60 years or more in length.

Future Plans: Move away from identifying what is out there to tackling the rescue aspect. This needs funding. They will continue to search repositories for data-at-risk and continue collaboration with GLOSS/DARTG to freshen on-line inventory. Collaborate with other programs (Atmospheric Circulation Reconstructions over the Earth (ACRE) meeting 11-2012). Eventually move to Phase II = recovery!

The third speaker, Stephen Del Greco from the US NOAA National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), spoke about environmental data through time and extending the climate record. (PDF of full paper) The NCDC is a weather archive with headquarters in Asheville, NC. It fulfills much of the nation’s climate data requirements. Their data comes from many different sources. Safe storage of over 5,600 terabytes of climate data (= 6.5 billion kindle books). How will they handle the upcoming explosion of data on the way? Need to both handle new content coming in AND provide increased access to larger amounts of data being downloaded over time. 2011 number = data download of 1,250 terabytes for the year. They expect that download number to increase 10 fold over the next few years.

The climate database modernization program went on over more than a decade rescuing data. It was well funded and millions of records were rescued with a budget of roughly 20 Million a year. The goal is to preserve and make major climate and environmental data available via the World Wide Web. Over 14 terabytes of climate data are now digitized. 54 million weather and environmental images are online. Hundreds of millions of records are digitized and now online. The biggest challenge was getting the surface observation data digitized. NCDC digital data for hourly surface observations generally stretch back to around 1948. Some historical marine observations go back to the spice trade records.

For international efforts they bring their imaging equipment to other countries where records were at risk. 150,000 records imaged under the Climate Database Modernization Program (CDMP).

Now they are moving from public funding to citizen-fueled projects via crowdsourcing such as the Zooniverse Program. Old Weather is a Zooniverse Project which uses crowdsourcing to digitize and analyze climate data. For example, the transcription done by volunteers help scientists model Earth’s climate using wartime ship logs. The site includes methods to validate efforts from citizens. They have had almost 700,000 volunteers.

Long-term Archive Tasks:

- Rescuing Satellite Data: raw images in lots of different film formats. All this is at risk. Need to get it all optically imaged. Looking at a ‘citizen alliance’ to do this work.

- Climate Data Records: Global Essential Climate Variables (ECVs) with Heritage Records. Lots of potential records for rescue.

- Rescued data helps people building proxy data sets: NOAA Paleoclimatology. ‘Paleoclimate proxies’ – things like boreholes, tree rings, lake levels, pollen, ice cores and more. For example – getting temperate and carbon dioxide from ice cores. These can go back 800,000 years!

We have extended the climate record through international collaboration. For example, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology provided daily temperature records for more than 1,500 additional stations. This meant a more than 10-fold increase in previous historical climate daily data holdings from that country.

Born Digital Maps

The final presentation discussed the map as a fundamental source of memory of the world, delivered by D. R. Fraser Taylor and Tracey Lauriault from Carleton University’s Geomatics and Cartographic Research Center in Canada. The full set of presentation slides are available online on SlideShare. (PDF of full paper)

We are now moving into born digital maps. For example, the Canadian Geographic Information System (CGIS) was created in the 1960s and was the worlds 1st GIS. Maps are ubiquitous in the 21st century. All kinds of organizations are creating their own maps and mash-ups. Community based NGOs, citizen science, academic and private sector are all creating maps.

We are loosing born digital maps almost faster than we are creating them. We have lost 90% of the born digital maps. Above all there is an attitude that preservation is not intrinsically important. No-one thought about the need to preserve the map – everyone thought someone else would do it. There was a complete lack of thought related to the preservation of these maps.

The Canada Land Inventory (CLI) was one of the first and largest born digital map efforts in the world. Mapped 2.6 million square kilometers of Canada. Lost in the 1980s. No-one took responsibility for archiving. Those who thought about it believed backup equaled archiving. A group of volunteers rescued the process over time – salvaged from boxes of tapes and paper in mid-1990s. It was caught just in time and took a huge effort. 80% has been saved and is now it is online. This was rescued because it was high profile. What about the low-profile data sets? Who will rescue them? No-one.

The 1986 BBC Doomsday Book was created in celebration of 900 years after William the Conqueror’s original Domesday Book. It was obsolete by the 1990s. A huge amount of social and economic information was collected for this project. In order to rescue it they needed an acorn computer and needed to be able to read the optical disks. The platform was emulated in 2002-2003. It cost 600,000 british pounds to reverse engineer and put online in 2004. New discs made in 2003 at the UK Archive.

It is easier to get Ptolomy’s maps from 15th century than it is to get a map 10 years old.

The Inuit Siku (sea ice) Atlas, an example of a Cybercartographic atlas, was produced in cooperation with Inuit communities. Arguing that the memory of what is happening in the north lies in the minds of the elders, they are capturing the information and putting it out in multi-media/multi-sensory map form. The process is controlled by the community themselves. They provide the software and hardware. They created a graphic tied to the Inuit terms for different types of sea ice. In some cases they record the audio of an elder talking about a place. The narrative of the route becomes part of the atlas. There is no right or wrong answer. There are many versions and different points of view. All are based on the same set of facts – but they come from different angles. The atlases capture them all.

The Gwich’in Place Name Atlas is building in the idea of long term preservation into the application from the start

The Cybercartographic Atlas of the Lake Huron Treaty Relationship Process is taking data from surveyors diaries from the 1850s.

There are lots of government of Canada geospatial data preservation intitatives, but in most cases there is a lot of retoric, but not so much action. There have been many consultations, studies, reports and initiatives since 2002, but the reality is that apart from the Open Government Consultations (TBS), not very much as translated into action. Even in the case where there is legislation, lots of things look good on paper but don’t get implemented.

There are Library and Archives Guidelines working to support digital preservation of geospatial data. The InterPares 2 (IP2) Geospatial Case Studies tackle a number of GIS examples, including the Cybercartographic Atlas of Antartica. See the presentation slides online for more specific examples.

In general, preservation as an afterthought rarely results in full recovery of born digital maps. It is very important to look at open source and interoperable open specifications. Proactive archiving is an important interim strategy.

Geospatial data are fundamental sources of our memory of the world. They help us understand our geo-narratives (stories tied to location), counter colonial mappings, are the result of scientific endeavors, represent multiple worldviews and they inform decisions. We need to overcome the challenges to ensure their preservation.

Q&A:

QUESTION: When I look at the work you are doing with recovering Inuit data from people. You recover data and republish it – who will preserve both the raw data and the new digital publication? What does it mean to try and really preserve this moving forward? Are we really preserving and archiving it?

ANSWER: No we are not. We haven’t been able to find an archive in Canada that can ingest our content. We will manage it ourselves as best we can. Our preservation strategy is temporary and holding, not permanent as it should be. We can’t find an archive to take the data. We are hopeful that we are moving towards finding a place to keep and preserve it. There is some hope on the horizon that we may move in the right directions in the Canadian context.

Luciana: I wanted to attest that we have all the data from InterPARES II. It is published in the final. I am jealously guarding my two servers that I maintain with money out of my own pocket.

QUESTION: Is it possible to have another approach to keep data where it is created, rather than a centralized approach?

ANSWER: We are providing servers to our clients in the north. Keeping copies of the database in the community where they are created. Keeping multiple copies in multiple places.

QUESTION: You mention surveys being sent out and few responses coming back. When you know there is data at risk – there may be governments that have records at risk that they are shy to reveal to the public? How do we get around that secrecy?

ANSWER: (IEDRO representative) We offer our help, rather than a request to get their data.

As is the case with all my session summaries, please accept my apologies in advance for any cases in which I misquote, overly simplify or miss points altogether in the post above. These sessions move fast and my main goal is to capture the core of the ideas presented and exchanged. Feel free to contact me about corrections to my summary either via comments on this post or via my contact form.

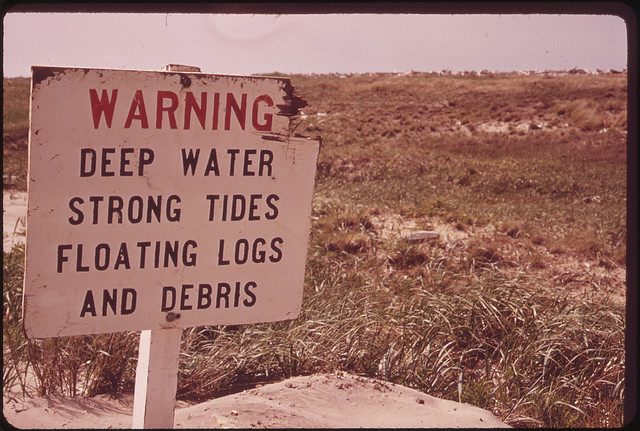

Image Credit: NARA Flickr Commons image “The North Jetty near the Mouth of the Columbia River 05/1973”

Updated 2/20/2013 based on presenter feedback.

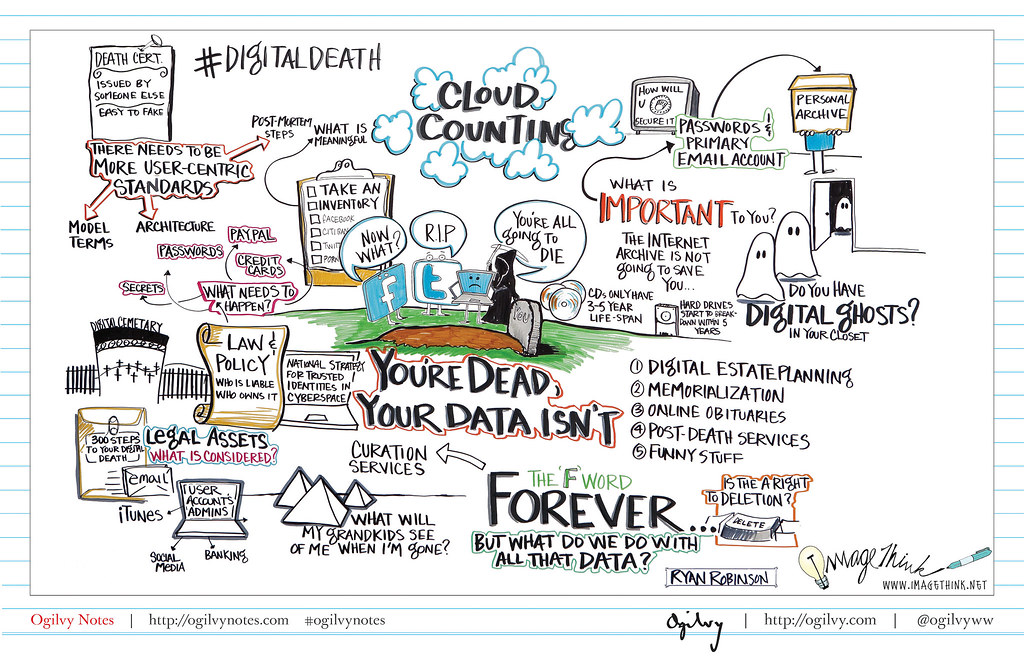

The second chapter in Partners for Preservation is ‘Curbing the Online Assimilation of Personal Information’ by Paulan Korenhof. Given the amount of attention being focused on the right to be forgotten and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), I felt it was essential to include a chapter that addressed these topics. Walking the fine line between providing access to archival records and respecting the privacy of those whose personal information is included in the records has long been an archival challenge.

The second chapter in Partners for Preservation is ‘Curbing the Online Assimilation of Personal Information’ by Paulan Korenhof. Given the amount of attention being focused on the right to be forgotten and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), I felt it was essential to include a chapter that addressed these topics. Walking the fine line between providing access to archival records and respecting the privacy of those whose personal information is included in the records has long been an archival challenge.

This friendly llama (spotted in the

This friendly llama (spotted in the

The

The