The official title of Session 203 was Getting Our Hands Dirty (and Liking It): Case Studies in Archiving Digital Manuscripts. The session chair, Catherine Stollar Peters from the New York State Archives and Records Administration, opened the session with a high level discussion of the “Theoretical Foundations of Archiving Digital Manuscripts”. The focus of this panel was preserving hybrid collections of born digital and paper based literary records. The goal was to review new ways to apply archival techniques to digital records. The presenters were all archivists without IT backgrounds who are building on others work … and experimenting. She also mentioned that this also impacts researchers, historians, and journalists.For each of the presenters, I have listed below the top challenges and recommendations. If you attended the sessions, you can skip forward to my thoughts.

Norman Mailer’s Electronic Records

Challenges & Questions:

- 3 laptops and nearly 400 disks of correspondence

- While the letters might have been dictated or drafted by Mailer, all the typing, organization and revisions done on the computer were done by his assistant Judith McNally. This brings into question issues of who should be identified as the record creator. How do they represent the interaction between Mailer & McNally? Who is the creator? Co-Creators?

- All the laptops and disks were held by Judith McNally. When she died all of her possessions were seized by county officials. All the disks from her apartment were eventually recovered over a year later – but it causes issues of provenance. There is no way to know who might have viewed/changed the records.

Revelations and Recommendations:

What is accessioning and processing when dealing with electronic records? What needs to be done?

- gain custody

- gather information about creator’s (or creators’) use of the electronic records. In March 2007 they interviewed Mailer to understand the process of how they worked together. They learned that the computers were entirely McNally’s domain.

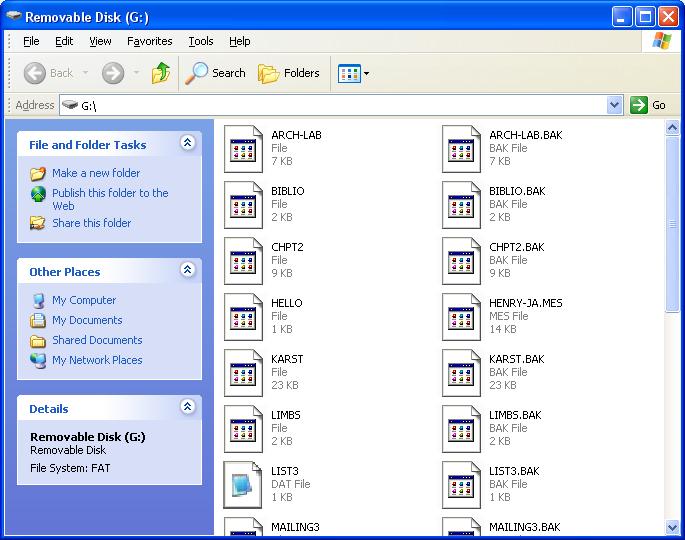

- number disks, computers (given letters), other digital media

- create disk catalog – to reflect physical information of the disk. Include color of ink.. underlining..etc. At this point the disk has never been put into a computer. This captures visual & spacial information

- gather this info from each disk: file types, directory structure & file names

The ideal for future collections of this type is archivist involvement earlier – the earlier the better.

Papers of Peter Ganick

- Speaker: Melissa Watterworth

- Featured Collection: Papers of Writer and Small Press Publisher Peter Ganick, Thomas J Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut

Challenges & Questions:

- What are the primary sources of our modern world?

- How do we acquire and preserve born digital records as trusted custodians?

- How do we preserve participatory media – maybe we can learn from those who work on performance art?

- How do we incrementally build our collections of electronic records? Should we be preserving the tools?

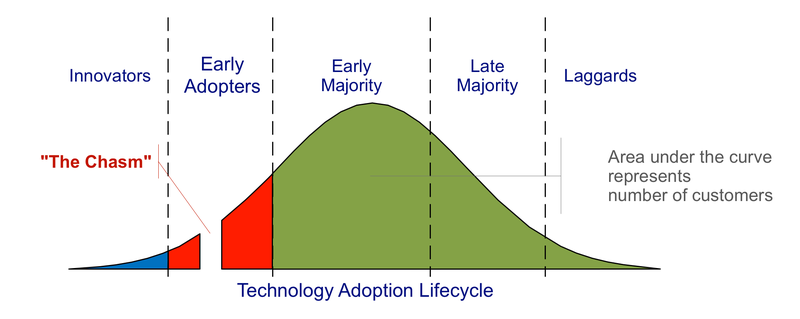

- Timing of acquisition: How actively should we be pursuing personal archives? How can we build trust with creators and get them to understand the challenges?

- Personal papers are very contextual – order matters. Does this hold true for born digital personal archives? What does the networking aspect of electronic records mean – how does it impact the idea of order?

- First attempt to accession one of Peter Ganick’s laptops and the archivist found nothing she could identify as files.. she found fragments of text – hypertext work and lots of files that had questionable provenance (downloaded from a mailing list? his creations?). She had to sit down next to him and learn about how he worked.

- He didn’t understand at first what her challenges were. He could get his head around the idea of metadata and issues of authenticity. He had trouble understanding what she was trying to collect.

- How do we arrange and keep context in an online environment?

- Biggest tech challenge: are we holding on for too long to ideas of original order and context?

- Is there a greater challenge in collecting earlier in the cycle? What if the creator puts restrictions on groupings or chooses to withdraw them?

- Do we want to create contracts with donors? Is that practical?

Revelations and Recommendations:

- Collect materials that had high value as born digital works but were at a high risk of loss.

- Build infrastructure to support preservation of born digital records.

- Go back to the record creator to learn more about his creative process. They used to acquire records from Ganick every few years.. that wasn’t frequent enough. He was changing the tools he used and how he worked very quickly. She made sure to communicate that the past 30 years of policy wasn’t going to work anymore. It was going to have to evolve.

- Created a ‘submission agreement’ about what kinds of records should be sent to the archive. He submitted them in groupings that made sense to him. She reviewed the records to make sure she understood what she was getting.

- Considering using PDFa to capture snapshot of virtual texts.

- Looked to model of ‘self archiving’ – common in the world of professors to do ongoing accruals.

- What about ’embedded archivists’? There is a history of this in the performing arts and NGOs and it might be happening more and more.

George Whitmore Papers

Challenges & Questions:

- How do you establish identity in a way that is complete and uncorrupted? How do you know it is authentic? How do you make an authentic copy? Are these requirements as unreasonable and unachievable?

Revelations and Recommendations:

- Refresh and replicate files on a regular schedule.

- They have had good success using Quick View Plus to enable access to many common file formats. On the downside, it doesn’t support everything and since it is proprietary software there are no long term guarantees.

- In some cases they had to send CP/M files to a 3rd party to have them converted into WordStar and have the ascii normalized.

- Varied acquisition notes.. and accession records.. loan form with the 3rd party who did the conversion that summarized the request.. they did NOT provide information about what software was used to convert from CP/M to DOS. This would be good information to capture in the future.

- Proposed an expansion of the standards to include how electronic records were migrated in the <processinfo> processing notes.

Questions & Answers

Question: As part of a writers community, what do we tell people who want to know what they can DO about their records. They want technical information.. they want to know what to keep. Current writers are aware they are creating their legacy.

Answer: Michael: The single best resource is the interPARES 2 Creator Guidelines. The Beineke has adapted them to distrubute to authors. Melissa: Go back to your collection development policies and make sure to include functions you are trying to document (like process.. distribution networks). Also communities of practice (acid free bits) are talking about formats and guidelines like that Gabriela: People often want to address ‘value’. Right now we don’t know how to evaluate the value of electronic drafts – it is up to authors.

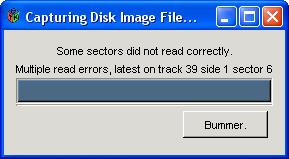

Question: Cal Lee: Not a question so much as an idea: the world of digital forensics and security and the ‘order of volatility’ dictate that everyone should always be making a full disk copy bit by bit before doing anything else.

Comment: Comment on digital forensic tools – there is lots of historical and editing history of documents in the software… also delete files are still there.

Question: Have you seen examples of materials that are coming into the archive where the digital materials are working drafts for a final paper version? This is in contrast to others are electronic experiments.

Answer: Yes, they do think about this. It can effect arrangement and how the records are described. The formats also impact how things are preserved.

Question: Access issues? Are you letting people link to them from the finding aids? How are the documents authenticity protected.

Answer: DSpace gives you a new version anytime you want it (the original bitstream) .. lots of cross linking supports people finding things from more than one path. In some cases documents (even electronic) can only be accessed from within the on site reading room.

Question: What is your relationship is like with your IT folks?

Answer: Gabriela: Our staff has been very helpful. We use ‘legacy’ machines to access our content. They build us computers. They are also not archivists, so there is a little divide about priorities and the kind of information that I am interested in.. but it has been a very productive conversation.

Question: (For Melissa) Why didn’t you accept Peter’s email (Melissa had said they refused a submission of email from Peter because it didn’t have research value)?

Answer: The emails that included personal medical emails were rejected. The agreement with Peter didn’t include an option to selectively accept (or weed) what was given.

Question: In terms of gathering information from the creators.. do you recommend a formal/recorded interview? Or a more informal arrangement in which you can contact them anytime on an ongoing basis?

Answer: Melissa: We do have more formal methods – ‘documentation study’ style approaches. We might do literature reviews.. Ultimately the submission agreement is the most formal document we have. Gabriela: It depends on what the author is open to.. formal documentation is best.. but if they aren’t willing to be recorded, then you take what you can get!

My Thoughts

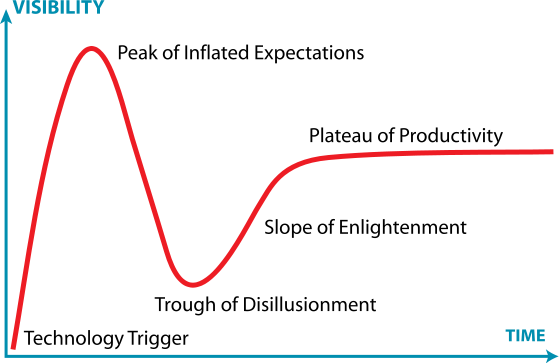

I am very curious to see how best practices evolve in this arena. I wonder how stories written using something like Google Documents, which auto-saves and preserves all versions for future examination, will impact how scholars choose to evaluate the evolution of documents. There have already been interesting examinations of the evolution of collaborative documents. Consider this visual overview of the updates to the Wikipedia entry for Sarah Palin created by Dan Cohen and discussed in his blog post Sarah Palin, Crowdsourced. Another great example of this type of visual experience of a document being modified was linked to in the comments of that post: Heavy Metal Umlaut: The Movie. If you haven’t seen this before – take a few minutes to click through and watch the screencast which actually lets you watch as a Wikipedia page is modified over time.

While I can imagine that there will be many things to sort out if we try to start keeping these incredibly frequent snapshot save logs (disk space? quantity of versions? authenticity? author preferences to protect the unpolished versions of their work?) – I still think that being able to watch the creative process this way will still be valuable in some situations. I also believe that over time new tools will be created to automate the generation of document evolution visualization and movies (like the two I link to above) that make it easy for researchers to harness this sort of information.

Perhaps there will be ways for archivists to keep only certain parts of the auto-save versioning. I can imagine an author who does not want anyone to see early drafts of their writing (as is apparently also the case with architects and early drafts of their designs) – but who might be willing for the frequency of updates to be stored. This would let researchers at least understand the rhythm of the writing – if not the low level details of what was being changed.

I love the photo I found for the top of this post. I admit to still having stacks of 3 1/2 floppy disks. I have email from the early days of BITNET. I have poems, unfinished stories, old resumes and SQL scripts. For the moment my disks live in a box on the shelf labeled ‘Old Media’. Lucky me – I at least still have a computer with a floppy drive that can read them!

Image Credit: oh messy disks by Blude via flickr.

As is the case with all my session summaries from SAA2008, please accept my apologies in advance for any cases in which I misquote, overly simplify or miss points altogether in the post above. These sessions move fast and my main goal is to capture the core of the ideas presented and exchanged. Feel free to contact me about corrections to my summary either via comments on this post or via my contact form.