Caffè Lena opened in Saratoga Springs, NY in May of 1960. Since then, the coffee house has kept its doors open featuring predominately performances by folk musicians. Often the performers were at the start of their careers. The café has featured now familiar songwriters including Bob Dylan, Arlo Guthrie, Ani DiFranco, and Kate and Anna McGarrigle – to name just a few. After the death of the founder, Lena Spencer, in 1989 Caffè Lena was converted to a non-profit institution.

The Caffè Lena History Project has launched an online searchable database for the complete Caffè Lena collection. The processing of this collection was made possible with support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, administered through the Council on Library and Information Resources’ Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives Project. The digitization of the material was made possible through generous funding from the EMC Corporation.

This collection is physically in many places, but the Omeka based website serves as a centralized index for browsing and discovering the rich set of papers, audio recordings, photographs and ephemera documenting the history of this performance space. The database was architected by Monte Evans, who managed to bring together all the large and disparate data sets and organize them within Omeka. This database is the third part of the overall history project, which also produced a three-CD set of audio recordings and a lavish book documenting the history of the coffee house through stories and many previously unseen photos.

Over the course of more than 10 years, this project has been a labor of love by Jocelyn Arem to hunt for long lost caches of materials – in attics and garages and archives across the country. Then her efforts moved on to digitization and promotion of the amazing materials she found. She was supported by many people (in addition to the funders) who helped move the work forward — including dedicated community members, volunteers, the Caffè Lena Board of Directors, and friends around the country who shared their expertise and support.

The video above is the ‘trailer’ for the project and does a great job introducing both Caffè Lena and the history project through interviews, photographs and audio clips.

The Database

The contents of the website are divided into three sections — recordings, ephemera and photographs. While it is possible to search across the full array of contents, there are additional options for filtering by tags and sorting within each sub-section of the database.

Of all the materials gathered during this project, the audio recordings were the most elusive. In many cases it required detective work to track down recordings that were remembered by some and forgotten by others. Recordings donated from as far away as Ontario and Ohio, and digitized by the GRAMMY Award-winning Magic Shop Studio in NYC. Jocelyn Arem shared with me one of her favorite stories of serendipity during the search for recordings – that of the ZBS Radio Series tapes. A former ZBS producer in Panama, Robert Durand, contacted them because he heard about the project online. He connected them with an engineer at ZBS in New York. As a result they received the edited Caffè Lena ZBS collection. However they always wondered where the unedited tapes had ended up. A few months later, Jocelyn followed a trail to another engineer who had left a note at the Caffè years earlier saying he had tapes to donate. Along with former Caffè Lena board member (and audio tape donor) Dick Kavanaugh, she drove to the mountains of upstate, NY to retrieve the tapes from this new donor and lo and behold … there was the unedited Caffè Lena tape collection!

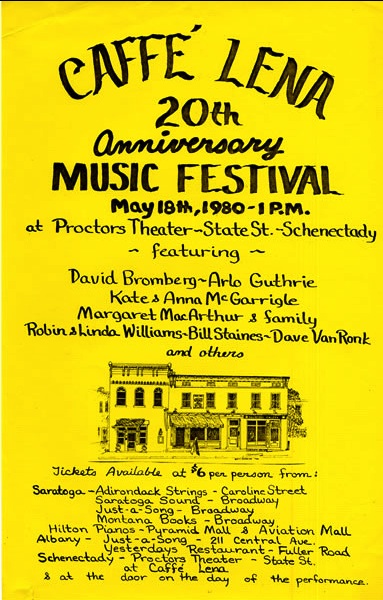

In the Recordings section of the site, you can find descriptive information about 514 recording now held by the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center.. The browse interface lets you filter by using a drop-down list of artist names. Occasionally the entries includes short audio samples you can listen to online, such as this one for Kate and Anna McGarrigle recorded during the 20th Anniversary Music Festival described on the flyer shown here. One thing that surprised me is that if sometimes an image will lead to a multi-page PDF. In the recording’s section this was common and the PDFs of the tape transfer reports include detailed notes about the recording.

The Ephemera section of the site features 32 boxes of materials from five separate collections, listed below.

- the Lena Spencer Papers, Performer Files and Jan Nargi Collections — all held by the Saratoga Springs History Museum,

- the Board of Directors Collection held by the American Folklife Center

- the Lively Lucys Coffeehouse Collection held by Skidmore College

Each collection can be browsed individually, with their own dedicated options of filtering by tags. Here it was a bit more obvious that the image you saw was likely just the first page of a multi-page folder digitized and presented as a single PDF.

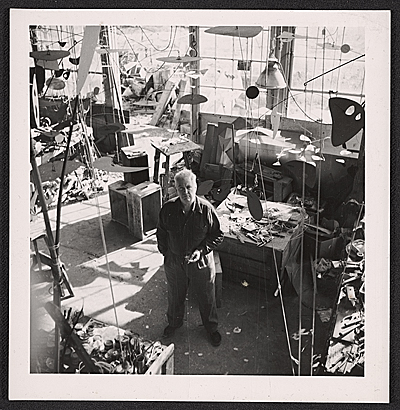

Finally, the Photographs section includes over 6,000 black and white photographs made by Joe Alper at Caffè Lena between 1960-1967. These images were catalogued and digitized by Edward Elbers and are held by the Joe Alper Photo Collection LLC. This section lets you filter by ‘artist’. For example, there are 296 photos of Bob Dylan.

Tagging and Controlled Vocabularies

One of the recurring challenges for those tagging content from multiple sources is the different versions of terms that mean the same thing. Controlled vocabularies are hard to enforce across different collections held by different organizations or individuals. In the case of the Caffè Lena History Project, I noticed that there were different values used for tagging across the materials. For example, the values used to tag and populate the list of recording artists’ names exactly match the names listed on the tape transfer reports. In some cases the same artist may be listed in multiple ways. For example, there are entries for The McGarrigles, Kate McGarrigle and Anna McGarrigle. Another example can be found in the tagging for materials related to Bob Dylan. Bob Dylan, bob, Dylan and Dylan Bob are all tags that give you different subsets of the search results that just searching on Dylan provides.

These types of issues are often compounded when materials come from so many different sources and through many different hands along the way. That said, the combination of artists lists, tags and search functions make it easy to discover materials related to your favorite folk music artists. Just keep in mind that looking for multiple versions of a performer’s name might help you find more materials.

Other Virtual Archives

The approach of creating a single website to unify materials that are not co-located but do all relate to a single unifying theme reminded me of two earlier projects: The Publishers’ Bindings Online (PBO) and the Greene & Greene Virtual Archive.

The Publishers’ Bindings Online project now features over 13,000 images online of over 5,000 book bindings from 1815 to 1930. These books are held in libraries at multiple institutions and the project’s success at (and challenges with) using a single unified vocabulary for tagging was discussed in detail during a session at SAA in 2007: Publishers’ Bindings Online – Digitization, Collaboration, Standardization and Community Building. I used the subject vocabulary to find a book cover featuring polar bears.

The Greene & Greene Virtual Archives presents materials of the southern California design firm Greene & Greene. Active from 1894-1922, they are associated with the architecture and craftsmanship of the American Arts and Crafts Movement. The Greene & Greene website presents images and metadata of a selected set of 4000 items held by four different repositories. They also provide links to the full descriptions of materials held by each of the repositories. The search functionality on the website is geared towards exploration of individual architectural projects, but also permits advanced search by topic, repository, location, document type and date. Unlike PBO and Caffè Lena, this site doesn’t expose the tagging that lets the results be returned by these groupings.

My Personal Connection

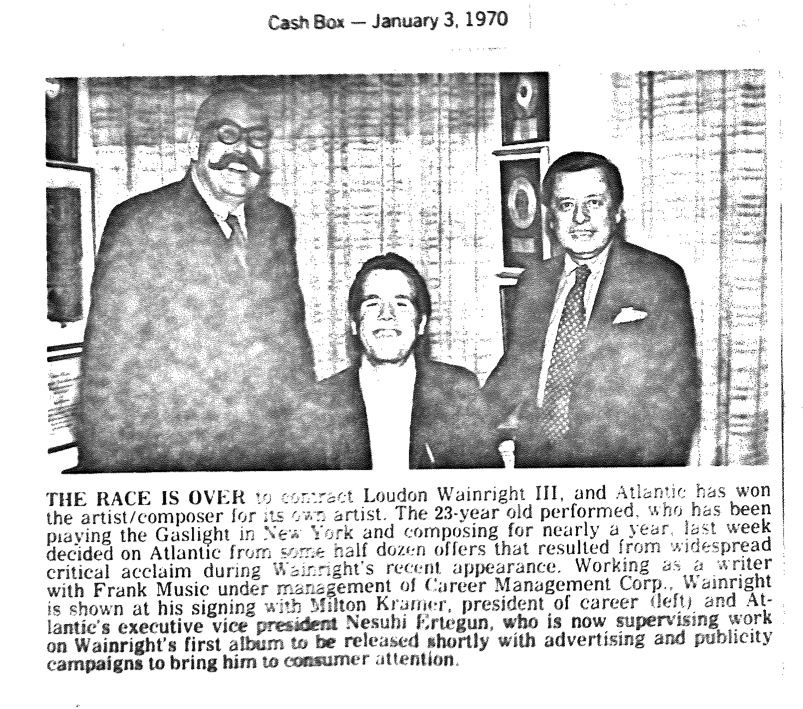

Finally, I would like to share my personal connection to this project. Jocelyn contacted me over a year ago while in the final stages of working on the book to ask if my father had taken a particular photo of Loudon Wainwright III. My father was his manager at the start of his career and did take many photos of him, though not the one in question.

After the launch of the site, I was curious to see what might be in the database related to Loudon and perhaps my father. I found this great photo in the Ephemera file for Wainwright Loudon. My father is the gentleman on the left with the mustache!

More about Caffè Lena

The book was released in October 2013. Soon to be available via a second printing direct from the publisher, you can still find copies of the first printing of Caffe Lena: Inside America’s Legendary Folk Music Coffeehouse on Amazon.com.

There is a traveling exhibit that can be brought to your local venue with tons of details available online. You can also subscribe to an online newsletter. If you have a project for which you would like to use any of the materials (audio included) – there is a form for making licensing requests.

Of course, one of the best sources of information about Caffè Lena and its founder are the materials featured on the history project website.

Finally, do you have materials to donate to the archive? You can contact the Caffè Lena History Project team directly via this online form.

Image Credits: Courtesy of the Caffè Lena Collection and the Saratoga Springs History Museum