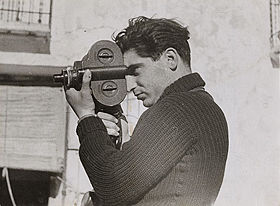

In the Washington Post article There Are No Black-and-White Answers in War — Then Lost Negatives Turn Up (February 1, 2008), we learn that three cardboard boxes of negatives were recently delivered to the International Center of Photography (ICP) – possibly including as many as 4,000 images. This collection of black-and-white film, consisting predominately of photos shot by Robert Capa during the Spanish Civil War, was long thought lost during World War II and will join the already existing Robert Capa Archives. The boxes also contain negatives from two other famed photographers associated with Capa, Gerda Taro and David Seymour (known by the pseudonym Chim – pronounced shim).

In the Washington Post article There Are No Black-and-White Answers in War — Then Lost Negatives Turn Up (February 1, 2008), we learn that three cardboard boxes of negatives were recently delivered to the International Center of Photography (ICP) – possibly including as many as 4,000 images. This collection of black-and-white film, consisting predominately of photos shot by Robert Capa during the Spanish Civil War, was long thought lost during World War II and will join the already existing Robert Capa Archives. The boxes also contain negatives from two other famed photographers associated with Capa, Gerda Taro and David Seymour (known by the pseudonym Chim – pronounced shim).

There are many reasons these boxes are exciting for historians and Capa researchers. They hold the promise of answering some long standing questions. Where certain famous photos were staged? Are the current credits given for various photos are correct? But what caught my eye in this article was the following quote from ICP curator Brian Wallis:

“Capa was really adept at creating a whole story in one day: Here are the characters, here is the beginning, the action shots, the end, and the effect on civilians. If you look at his work not as great individual shots, but as stories, you get a completely different picture of him, and I think a more accurate and valuable picture.

“These negatives will further amplify that story, not just a few stories but dozens of stories that went out. It is like a sketchbook — he was trying out various ideas, and some worked and some didn’t.”

What About Digital Photographer’s Sketchbooks?

If you have ever used a digital camera, you have almost certainly enjoyed the instant gratification of being able to preview your photos on the tiny screen. The next temptation is to click the delete button. Sometimes you delete because the photo is clearly not what you were after – other times you delete to make room for some much more crucial photo.

I don’t know what the standard best practices are for professional photographers. Part of me hopes that they keep everything – at least until they can view the images on a big screen. But there is clearly a much easier path to deleting the ideas that didn’t work out. It leaves me wondering what the scholars of the future will be missing by not being able to see the failed experiments. The ‘sketchbooks’ of digital photographers could easily be perceived as at risk records. That said, many creative individuals (artists, architects, photographers… etc) do not care to share their failed experiments with the outside world. One of the issues facing those preserving digital records of the design community is the strong desire of designers to not share their work in progress and only share the final product (see my post SAA2007: Preserving Born Digital Records of the Design Community (Session 106) for more thoughts on this).

Image Overload

Of course there will be the photographers who do keep everything. Hard drive space is getting cheaper with every passing day. Perhaps my fears are misplaced and instead we should be worrying more about the flood of photographs that will overwhelm archivists and researchers. The time needed to discover the ‘good’ and ‘important’ photographs in a collection of thousands of images could be extreme.

I shoot all my photos digitally now. I no longer live in a world where there are only 36 shots on a single role – I don’t need to choose each photo carefully. I cheerfully tell my friends “Photos are free!”. Even that doesn’t stop me from deleting the ones that I really dislike. Sometimes the 2 GB card in my camera gets full before an event is done, so the on the spot weeding of photos occurs as well. But when I compare the number of ‘good’ photos that I have uploaded to share online (currently 5,000+ and counting) with the number of photos I have on my hard drive (20,000+) it is clear to me that I am keeping plenty of ‘sketch photos’. It is also interesting to note that I will often realize that there are photos I really like now that I didn’t appreciate immediately after they were taken. While something at the time made me NOT include it as a photo to share, now I see something in the image that catches my eye in a new way. The more this happens, the less I delete as I download, organize and tag my photos.

Metadata and the Exchangeable Image File Format (EXIF)

Of course the situation with digital photographs is not all bad. When digital cameras record a photo, they also record a set of metadata in the exchangeable image file format (EXIF) format. The metadata recorded usually includes camera make and model, date, time, and camera settings. Some cameras can even record GPS generated location information. Because there is no way to know the time zone (at least without location information), the value of the time setting is more useful for relating photos from within a set to one another than in establishing the actual time a photo was taken.

Adobe has contributed their own proprietary metadata format called Extensible Metadata Platform (XMP).

The most common metadata tags recorded in XMP data are those from the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative, which include things like title, description, creator, and so on. The standard is designed to be extensible, allowing users to add their own custom types of metadata into the XMP data. (Wikipedia Entry: Extensible Metadata Platform )

The magic of both XMP and EXIF is that the metadata is embedded in the file itself. There is no chance of losing the connection between a photo and the information about it – it is akin to writing on the back of an analog photograph. Embedded metadata provides the greatest tool for rediscovering the original order in which a series of photographs were taken, as well as providing access to metadata entered by the photographer at the image level.

The archivist of today accessioning born digital images must be comfortable with tools for viewing and updating embedded metadata. I mention updating because any information that is currently known about an image that could be added to the embedded metadata is more information that cannot later become accidentally separated from the images in question. This of course assumes that we will still have the proper technology in the future with which to access all this embedded metata.

Embedded metadata can be updated before it reaches the controlled environment of an archive. Data found as embedded metadata must be evaluated in the same manner that any information about photographs would be evaluated. For example, it would be a lot easier to modify metadata on digital photos to make the images appear to have been taken in a different order than it would be to do the same change with a strip of analog negatives. If this in fact was done – the fact that it was would likely be as interesting to researchers as the original order (assuming of course that you could ever figure out that such a modification had been made!).

Not all methods of organizing photos results in embedded metadata, so there is plenty of room for the standard challenges of old software that you can’t get to run but that holds the key to information about a hard drive of thousands of images. Sophisticated photograph management tools often now include workflow features that could also provide insight into the decision making and processing steps taken by a photographer. Much of this type of information is very unlikely to be embedded in the photos themselves – but still would represent interesting digital records related to the everyday work that a professional photographer performs.

Final Thoughts

I do feel that something is being lost via the ease with which one may delete experimental ‘sketchbook’ photos, but I suspect that the lure of virtually infinite hard drive space, image organization/tagging software tools and the clues provided by embedded metadata will balance the scales. Those who study photographers and their work will certainly have more to say about far in the future. There will be hard choices over the next decades – what can we do to guarantee access in that distant time to the full digital bodies of work of the Capas of today? I think the answers start with building strong lines of communication between prominent digital photographers and archivists. I know that this is just a special case of the challenges we see with digital records across professions, but each field adds its own special issues that must be sorted through and figured out one at a time. So, are there archivists out there working with professional digital photographers?

For more images related to this story, see the New York Time’s slideshow about Robert Capa’s Lost Negatives [UPDATE: New images available in the slideshow Inside the Mexican suitcase, posted April 29, 2009]

Image credit: Photographer Robert Capa during the Spanish civil war, May 1937. Photo by Gerda Taro. If the logic on this Wikimedia Commons page is to believed, this photo is in the public domain in the United States because the photographer died in 1937 (ie, more than 70 years ago).