The official title for this session is “Preservation and Conservation of Captured and Born Digital Materials” and it was divided into three presentations with introduction and question moderation by Jordon Steele, University Archivist at Johns Hopkins University.

Digital Curation, Understanding the lifecycle of born digital items

Isaiah Beard, Digital Data Curator from Rutgers, started out with the question ‘What Is Digital Curation?’. He showed a great Dilbert cartoon on digital media curation and the set of six photos showing all different perspectives on what digital curation really is (a la the ‘what I really do’ meme – here is one for librarians).

“The curation, preservation, maintenance, collection and archiving of digital assets.” — Digital Curation Center.

What does a Digital Curator do?

Aquire digital assets:

- digitized analog sources

- assets that were born digital, no physical analog exists

Certify content integrity:

- workflow and standards and best practices

- train staff on handling of the assets

- perform quality assurance

Certify trustworthiness of the architecture:

- vet codecs and container/file formats – must make sure that we are comfortable with the technology, hardware and formats

- active role in the storage decisions

- technical metadata, audit trails and chain of custody

Digital assets are much easier to destroy than physical objects. In contrast with physical objects which can be stored, left behind, forgotten and ‘rediscovered’, digital objects are more fragile and easier to destroy. Just one keystroke or application error can destroy digital materials. Casual collectors typically delete what they don’t want with no sense of a need to retain the content. People need to be made aware that the content might be important long term.

Digital assets are dependent on file formats and hardware/software platforms. More and more people are capturing content on mobile devices and uploading it to the web. We need to be aware of the underlying structure. File formats are proliferating and growing over time. Sound files come in 27 common file formats and 90 common codecs. Moving images files come in 58 common containers/codecs and come with audio tracks in the 27 file formats/90 common codecs.

Digital assets are vulnerable to format obsolescence — examples include Wordperect (1979), Lotus 1-2-3 (1978) and Dbase (1978). We need to find ways to migrate from the old format to something researchers can use.

Physical format obsolescence is a danger — examples include tapes, floppy disk, zip disk, IBM demi-disk and video floppy. There is a threat of a ‘digital dark age’. The cloud is replacing some of this pain – but replacing it with a different challenge. People don’t have a sense of where their content is in the physical world.

Research data is the bleeding edge. Datasets come in lots of different flavors. Lots of new and special file formats relating specifically to scientific data gathering and reporting… long list including things like GRIB (for meterological data), SUR (MRI data), DWG (for CAD data), SPSS (for statistical data from the social sciences) and on and on. You need to become a specialist in each new project on how to manage the research data to keep it viable.

There are ways to mitigate the challenges through predictable use cases and rigid standards. Most standard file types are known quantities. There is a built-in familiarity.

File format support: Isaiah showed a grid with one axis Open vs Closed and the other Free vs Proprietary. Expensive proprietary software that does the job so well that it is the best practice and assumed format for use can be a challenge – but it is hard to shift people from using these types of solutions.

Digital Curation Lifecycle

- Objects are evaluated, preserve, maintained, verified and re-evaluated

- iterative – the cycle doesn’t end with doing it just once

- Good exercise for both known and unknown formats

The diagram from the slide shows layers – looks like a diagram of the geologic layers of the earth.

Steps:

- data is the center of the universe

- plan, describe, evaluate, learn meanings.

- ingest, preserve curate

- continually iterate

Controlled chaos! Evaluate the collection and needs of the digital assets. Using preservation grade tools to originate assets. Take stock of the software, systems and recording apparatus . Describe in the tech metadata so we know how it originated. We need to pick our battles and need to use de facto industry standards. Sometimes those standards drive us to choices we wouldn’t pick on our own. Example – final cut pro – even though it is mac and proprietary.

Establish a format guide and handling procedures. Evaluate the veracity and longevity of the data format. Document and share our findings. Help others keep from needing to reinvent the wheel.

Determine method of access: How are users expected to access and view these digital items? Software/hardware required? View online – plug-in required? third party software?

Primary guidelines: Do no harm to the digital assets.

- preservation masters, derivatives as needed

- content modification must be done with extreme care

- any changes must be traceable, audit-able, reversible.

Prepare for the inevitable: more format migrations. Re-assess the formats.. migrate to new formats when the old is obsolete. Maintain accessibility while ensuring data integrity.

At Rutgers they have the RUcore Community Repository which is open source, and based on FEDORA. It is dedicated to the digital preservation of multiple digital asset types and contains 26,238 digital assets (as of April 2012). Includes audio, video, still images, documents and research data. Mix of digital surrogates and born digital assets.

Publicly available digital object standards are available for all traditional asset types. Define baseline quality requirements for ‘reservation grade’ files. Periodically reviewed and revised as tech evolves. See Rutgers’ Page2Pixel Digital Curation standards.

They use a team approach as they need to triage new asset types. Do analysis and assessment. Apply holistic data models and the preservation lifecycle and continue to publish and share what they have done. Openness is paramount and key to the entire effort.

More resources:

The Archivist’s Dilemma: Access to collections in the digital era

Next, Tim Pyatt from Penn State spoke about ‘The Archivist’s Dilemma’ — starting with examples of how things are being done at Penn State, but then moving on to show examples of other work being done.

There are lots of different ways of putting content online. Penn State’s digital collections are published online via ContentDM, Flickr, social media and Penn State IR Tools. The University Faculty Senate put up things on their own. Internet Archive. Custom built platform. Need to think about how the researcher is going to approach this content.

With analog collections that have portions digitized they describe both, but then includes a link to digital collection. These link through to a description of the digital collection.. and then links to CONTENTdm for the collection itself.

Examples from Penn State:

- A Google search for College of Agricultural Science Publications leads users to a complimentary/competing site with no link back to the catalog nor any descriptive/contextual information.

- Next, we were shown the finding aid for William W. Scranton Papers from Penn State. They also have images up on Flickr ‘William W. Scranton Papers’ . Flickr provides easy access, but acts as another content silo. It is crucial to have metadata in the header of the file to help people find their way back to the originating source. Google Analytics showed them that 8x more often content is seen in Flickr than CONTENTdm.

- The Judy Chicago Art Education Collection is a hybrid collection. The finding aid has a link to the curriculum site. There is a separate site for the Judy Chicago Art Education Collectiion more focused on providing access to her education materials.

- The University Curriculum Archive is a hybrid collection with a combination of digitized old course proposals, while the past 5 years of curriculum have been born digital. They worked with IT to build a database to commingle the digitized & born digital files. It was custom built and not integrated into other systems – but at least everything is in one place.

Examples of what is being done at other institutions:

PennState is loading up a Hydra repository for their next wave!

Born-Digital @UVa: Born Digital Material in Special Collections

Gretchen Gueguen, UVA

Presentation slides available for download.

AIMS (An Inter-Institutional Model for Stewardship) born digital collections: a 2 year project to create a framework for the stewardship of born-digital archival records in collecting repositories. Funded by Andrew W. Mellon Foundation with partners: UVA, Stanford, University of Hull, and Yale. A white paper on AIMS was published in January 2012.

Parts of the framework: collection development, accessioning, arrangement & description, discovery & access are all covered in the whitepaper – including outcomes, decision points and tasks. The framework can be used to develop an institutionally specific workflow. Gretchen showed an example objective ‘transfer records and gain administrative control’ and walked through outcome, decision points and tasks.

Back at UVA, their post-AIMS strategizing is focusing on collection development and accessioning.

In the future, they need to work on Agreements: copyright, access & ownership policies and procedures. People don’t have the copyright for a lot of the content that they are trying to donate. This makes it harder, especially when you are trying to put content online. You need to define exactly what is being donated. With born digital content, content can be donated multiple places. Which one is the institution of record? Are multiple teams working on the same content in a redundant effort?

Need to create a feasibility evaluation to determine systematically if something is it worth collecting. Should include:

- file formats

- hardware/software needs

- scope

- normalization/migration needed?

- private/sensitive information

- third-party/copyrighted information?

- physical needs for transfer (network, storage space, etc.)

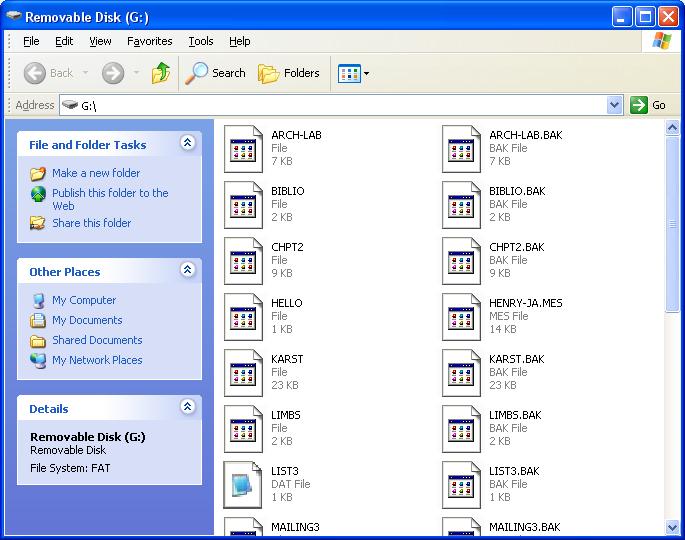

If you decide it is feasible to collect, how do you accomplish the transfer with uncorrupted data, support files (like fonts, software, databases) and ‘enhanced curation’? You may need a ‘write blocker’ to make sure you don’t change the content just by accessing the disk. You may want to document how the user interacted with their computer and software. Digital material is very interactive – you need to have an understanding of how the user interacted with it. Might include screen shots.

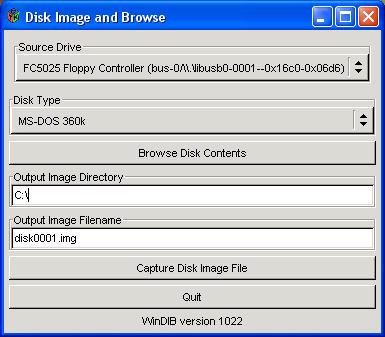

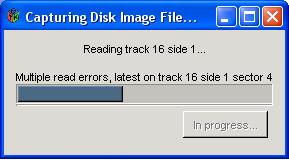

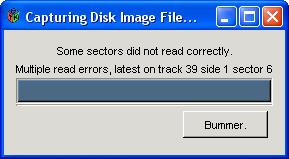

Next she showed their accessioning workflow:

- take the files

- create a disk image – bit for bit copy – makes the preservation master

- move that from the donor’s computer to their secure network with all the good digital curation stuff

- extract technical metadata

- remove duplicates

- may not take stuff with PPI

- triage if more processing is necessary

Be ready for surprises – lots of things that don’t fit the process:

- 8″ floppy disk

- badly damaged CD

- disk no longer functions – afraid to throw away in case of miracle

- hard drive from 1999

- mini disks

These have no special notation taken of them in the accessioning.

Priorities with this challenging material:

- get the data of aging media

- put it someplace safe and findable

- inventory

- triage

- transfer

Forensic Workstation:

- FRED = forensic recovery of evidence device – built in ultra bay writeblocker with usb, firewire, sata, csi, ide ad molex for power- external 5.25 floppy drive, cd/dvd/blu-ray, microcard reader, LTO tape drive, external 3.5″ drive + external hard drive for additional storage.

- toolbox

- big screen

FRED’s FDK software shows you overview of what is there, recognizes 1,000s of file format, deleted data, finds duplicates, and can identify PPI. It is very useful for description and for selecting what to accession – but it costs a lot and requires an annual license.

BitCurrator is making an open source version. From their website: “The BitCurator Project is an effort to build, test, and analyze systems and software for incorporating digital forensics methods into the workflows of a variety of collecting institutions.”

Archivematica:

- creates PREMIS record recording what activities are done – preservation metadata standard

- creates derivative records – migration!!

- yields a preservation master + access copies to be provided in the reading room

Hoping for Hypatia like thing in the future

Final words: Embrace your inner nerd! Experiment – you have nothing to loose. If you do nothing you will lose the records anyway.

Questions and Answers

QUESTION: How do you convince your administration that this needs to be a priority?

ANSWER:

Isaiah: Find examples of other institutions that are doing this. Show them that our history is at risk moving forward. A digital dark age is coming if we don’t do something now. It is really important that we show people “this is what we need to preserve”

Tim: Figure out who your local partners are. Who else has a vested interest in this content? IT was happy at Penn State that they didn’t need to keep everything – happy that there is an appraisal process.. and that they are preserving content so it doesn’t need to be kept by everyone. I am one of the authors of the upcoming report on born digital records — end of the summer: Association of Research Libraries – Managing Electronic Records – Spec Kit

Gretchen: Numbers are really useful. Sometimes you don’t think about it, but it is a good practice to count the size of what you created. How much time would it take to recreate it if you lost it. How many people have used the content? Get some usage stats. Who is your rival and what are their statistics?

Jordon: Point to others who you want to keep up with

QUESTION: would the panelists like to share experiences with preserving dynamic digital objects like databases?

ANSWER:

Isaiah: We don’t want to embarrass people. We get so many different formats. It is a trial and error thing. You need to say gently that there is a better way to do this. Sad example – burned DVDs from tapes in 2004.. got them in 2007. The DVDs were not verified. They were not stored well – stored in a hot warehouse. Opened the boxes and found unreadable DVDs – delaminating.

Tim: From my Duke Days, we had a number of faculty data sets in proprietary formats. We would do checksums on them, wrap them up and put them in the repository. They are there.. but who knows if anyone will be able to read them later. Same as with paper – preserve them now in good acid-free papers.

Gretchen: My 19 yo student held up a zip disk and said “Due to my extreme youth I don’t know what this is!” (And now you know why there is a photo of a zip disk at the top of this post – your reward for reading all the way to the end!)

Image Credit: ‘100MB Zip Disc for Iomega Zip, Fujifilm/IBM-branded‘ taken by Shizhao

As is the case with all my session summaries from MARAC, please accept my apologies in advance for any cases in which I misquote, overly simplify or miss points altogether in the post above. These sessions move fast and my main goal is to capture the core of the ideas presented and exchanged. Feel free to contact me about corrections to my summary either via comments on this post or via my contact form.